Coquitlam RCMP had their hands full dealing with a rash of homicides and sex crimes in the late 1990s -- one reason why convicted serial killer Robert Pickton was able to get away with his crimes for so long, according to an internal RCMP report obtained by CTV News.

Those crimes overwhelmed the detachment's 12-member major crimes team, which was also facing a staff shortage because many members were doing double duty, while other investigators doubted whether a crime had even occurred, the report says.

"While working sporadically on the file, numerous other high priority investigations, including a rash of homicides in Coquitlam Detachment jurisdiction took precedence," wrote Insp. R. J. Williams of Alberta's K Division RCMP.

But Williams could find no fault with officers on the ground in his conclusion, which was based on numerous interviews with officers stationed in Coquitlam between 1997 and 2002.

"Based on our experience and the interviews conducted, it is suffice to say nothing would have changed dramatically if those involved had to do it again," he wrote.

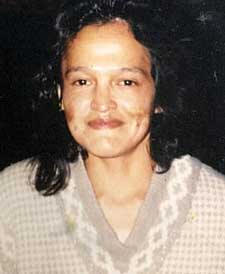

The 275-page, heavily redacted report was authored by RCMP from K Division in Alberta in response to "current and anticipated civil litigation," including lawsuits from the family of missing women Marcella Crieson and Andrea Joesbury. It was obtained by CTV News through an access to information request.

That's in contrast to a similar report by the Vancouver Police Department, which was released in its entirety to media and accepted that had investigators operated differently, lives could have been saved.

"No one wanted to let a killer escape," Deputy Chief Doug LePard said at an August press conference. "Everybody was doing their best, but when you don't have the right information, the right people aren't talking to each other, then mistakes happen, opportunities are lost."

Insp. Tim Shields of E-Division told CTV News Tuesday that the report isn't the final word on the matter.

"That report was created in 2002," he said. "We now have an upcoming public inquiry, and we believe that this independent inquiry is the best way for the organization to refine our tactics against major crimes."

Pickton is serving a life sentence in federal prison after being convicted on six counts of second-degree murder. He was also charged with 21 other counts, but prosecutors stayed those charges after the conviction.

Much of that evidence was gleaned during a major file review by a joint task force of E-Division RCMP and the Vancouver Police, which started after 2001.

But what hasn't been reviewed directly is the conduct of the RCMP in Coquitlam, the jurisdiction where Pickton lured, killed, butchered and eventually disposed of the bodies of as many as 49 women.

The redacted review makes little mention of an attempted murder charge against Pickton in 1997 of a prostitute who testified she escaped from Pickton's Port Coquitlam property.

Officers say they were first made aware of the case by a call from the Vancouver Police Department in "about 1997" to co-ordinate an investigation into some 23 missing women identified by the municipal police force.

But officers were having trouble keeping pace, said Earl Moulton, who was Chief Superintendent of the force at that time.

"There was a constant stream of sexual assaults, both historic and fresh, some murders around that time frame in terms of the Karaoke Murder, the E Lobster murder, the domestic violence murder on the hill with the three dead," Moulton said.

Moulton said he moved as many resources as he could into Pickton.

Some of the other crimes referred to in the report include a triple murder in 1999, where the bodies of an elderly couple and a young woman were found. The report says the "Karaoke murder" involved six culprits and one victim.

Another investigating officer, Sgt. Mike Connor, said that of the 12 members of the major crimes detachment, there were only 9 available, and three of those were gone on an investigation called "E-Lobster."

"This left six which throughout the summer you know you're only dealing with people on holidays and away and can't get them back," said Connor. "So probably at best we were only dealing with four or five members from our Major Crime Unit here. Far short of…far short of what was needed."

Staff Sergeant Brad Zalys, who was the serious crime sergeant at the time, said officers were torn between Pickton and other investigations.

"It was one of those ones that yeah, you were supposed to work on it, but every time the guys would try to get together and do something on it, something else would come in and I would go and see Earl (Moulton) and say what would you like us to do with this, do you want us to continue on with that or you want us to do this one and he'd say no, we have to do this one now, that's the priority," he said.

Zalys also said there was some skepticism that there was even a case to be made among officers.

"There was…a strong opinion from some of the members… that it was all bogus and there was nothing to it," he said. "The fact that there's no bodies were ever turning up from the women missing out of Vancouver that, gee … that created doubt in people's minds and that maybe there's someone else responsible."